Since the second caveman drew a buffalo on a cave wall, remakes and reimaginings have been an undeniable part of art. Filmmaking, despite being a new medium, is no exception to this rule. From Disney’s rebranded classics to timeless stories being told from different point-of-views, films are being re-made all the time. America hosts the biggest film studios in the world, and much of the time, the world watches whatever we decide to film. But this relationship goes both ways: Americans can’t get enough of remaking foreign films.

Since the mid-1940’s, American film producers and industry heads have metaphorically been in front row seats for every major motion picture, all around the world. These foreign films tell stories, not of violence or the American dream, but of emotional struggles and interpretations of folklore. Sometimes, an idea strikes a chord, and a few of these producers decide that they want those kinds of stories told in America. Most of the time, much to the dismay of the original writers and director, these producers don’t want to put the original film onto the big silver screen. So, what do these producers typically do? They buy the rights to the original film. Then, they sell the idea of a remake to a major (or minor) studio.

Following the sale, the producer works with the studio to bring on a new writer and director. Although in recent years, many studios and producers have been kind enough to work with and consult the original creators, this doesn’t take away from the process being repeated again and again.

Examples of this are spread out all through the history of American cinema. Some notable examples include timeless classics. The Western genre, stories of outlaws, robberies, and the lawless American west, has a bundle of films that were pivotal in the surge of American remakes.

One of the earliest examples of this phenomenon is The Magnificent Seven. Directed by John Sturges and written by William Roberts, this 1960 film is in fact a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. When released in 1954, many critics compared Kurosawa’s film to westerns in America, since the directing style and the writing was incredibly similar. For the remake, the plot was heavily reworked. Samurai switched to Gunslingers, the Time Period was shifted 300 years further, and the location was switched from Japan to America. Ultimately, the remake was a huge success, matching the success of its Japanese origins. Unfortunately, Kurosawa and the Japanese writers went uncredited in the remake.

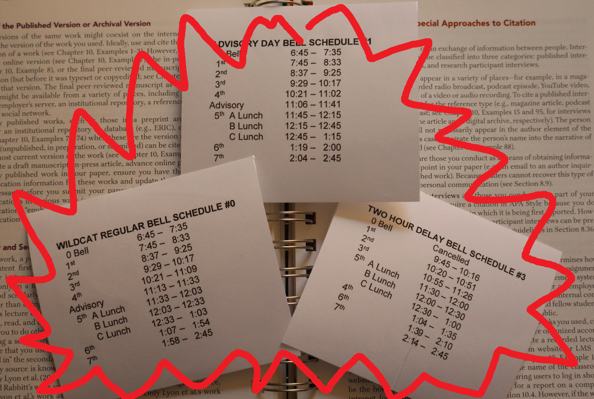

This process was not only repeated with films, but with some of the most popular television shows in recent history. Most notably, The Office. That’s right, what may be your favorite show actually originated in Britain. First airing in July of 2001, the series was met with very positive reviews. Unfortunately, this show would end up in the process that many films suffered prior. Although The Office UK only lasted two seasons, the remake lasted nine seasons. This is a clear example of a remake being more successful than its original.

There is just one question plaguing this industry. Plaguing these remakes. That question: Why? The short answer is money. Movies make money. Whether it’s an original film, a sequel, a remake, or even a straight-to-streaming film, it is going to make money. Films that are considered box office failures still make money. Are those successful? No, but they still turn a profit.

There is a longer answer though, America has a consistent need to own things. The American film industry is not the only film industry making remakes of foreign films. Britain, Japan, India, and almost every sovereign state with a film industry remakes foreign films. Britain remakes Indian films, Japan remakes British films, the phenomenon is not exclusive to the United States. Here’s where it gets you; can you name any British remakes of foreign films? How about Indian or Japanese remakes? If you can, you’re in the minority. Why do you think that is? American remakes are infused with millions of dollars and (usually) a very competent marketing campaign. It goes both ways, though. In India, any average citizen could name any Indian remake of a foreign film. Same goes for Britain or Japan. Their citizens are preview to their remakes, as are we with ours.

At the end of the day, American remakes are not slowing down and are never going to stop. The constant need to have something for our own is just part of us. Whether we’re working with the original creators or blatantly stealing plots from other films, it will still never end. Think about your favorite movie, or show, or both. Is it a remake? We urge you to find out, because it may broaden your horizons.